Smithsonian Scientists Dust Off Enigmatic Fossil Whale, Hone View of Toothy Whale

In Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, the book’s narrator, a sailor named Ishmael, presents a painstaking mid-19th-century classification of the whales that he encountered during his maritime career sailing the open seas. More than 160 years later, little of Ishmael’s proposed classification remains intact, having given way to countless revisions in scientific understanding of the evolution and diversity of living whales.

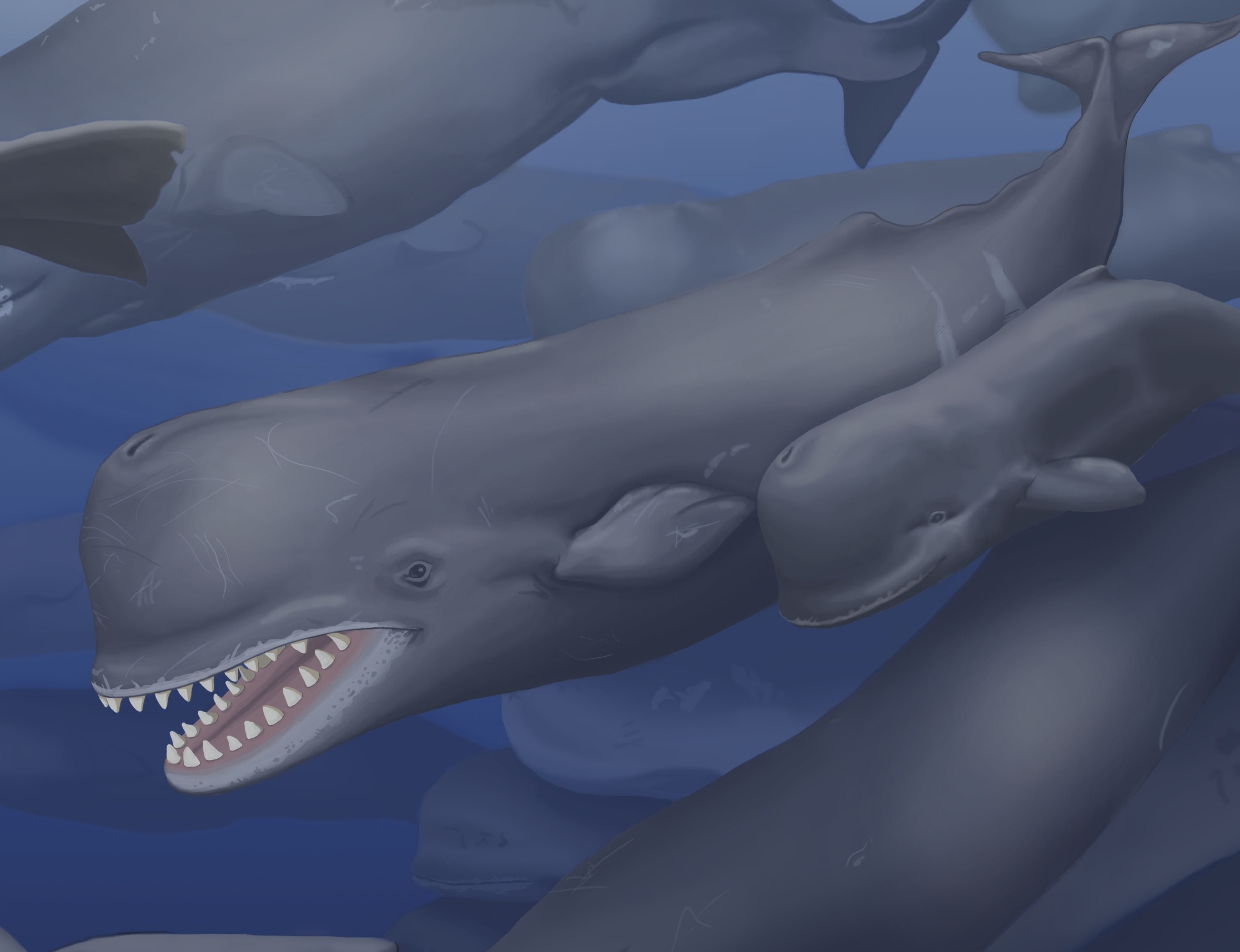

Now, scientists with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History are re-examining the classification of an extinct 15 million-year-old fossil sperm whale. The fossil whale was originally described and named in 1925 by Smithsonian scientist Remington Kellogg as Ontocetus oxymycterus, but Kellogg miscategorized it as belonging to a group of extinct walruses. In re-examining this fossil sperm whale for the first time in 90 years, the team created an entirely new group in the sperm whale family, Albicetus, and introduced the species, Albicetus oxymycterus, to a new branch on the sperm whale family tree. The scientists contend that the toothy fossil provides evidence of ancient seas rich in the number and diversity of marine mammals. Their findings are published in the Dec. 9 issue of the scientific journal PLOS ONE.

The fossils of this sperm whale, which represent the animal’s skull, jaws and teeth, date 14–16 million years ago, in a time known as the Middle Miocene, and were found in California in the 1880s. Because of the fossils’ bone-white color, the research team decided to name the new genus Albicetus, translating to “white whale,” in honor of Melville’s famous leviathan.

“While we don’t know what its skin color in life actually looked like, the color of the fossil is an ashen white,” said Nick Pyenson, curator of marine mammals in the museum’s Department of Paleobiology. “It only seemed appropriate to evoke Melville’s white sperm whale, Moby Dick, especially since we studied A. oxymycterus alongside the skeletons of some of its modern-day relatives in the collections here at the Smithsonian.”

In addition to studying the fossil itself, the team compared the jaw bones and other pieces to the corresponding anatomy from 36 other sperm whale specimens, both existing and extinct species held in the museum’s collections.

“The sheer size of this fossil, especially the block that preserves the skull and jaws, is impressive,” Pyenson said. “It probably weighs several hundred pounds and required a lot of muscle just to move around. It’s only with recent advancements in 3-D digitization that we were able to capture the entire geometry of this specimen and better understand the unusual anatomy of this extinct species of sperm whale.”

“One of our most important findings in studying Albicetus was that it not only represented an entirely new genus of fossil sperm whale, but it also prompted us to look where exactly Albicetus fit into the evolution of sperm whales,” said Alexandra Boersma, the team’s lead author and a research student at the museum during the time of research. “Modern sperm whales are unique in the whale world, with their ability to dive nearly two kilometers and their complex social groups, and they have the largest brains of any creature alive today. Understanding the evolutionary context in which living sperm whales evolved has a lot of implications for disciplines outside of paleobiology.”

Sperm whales are among the oldest lineages of Cetacea (the scientific term for all whales, dolphins and porpoises), with the oldest known specimen dating to about 25 million years ago. A phylogenetic analysis of A. oxymycterus, along with other fossil and living sperm whale species, revealed it to be what is known as a “stem” species in the sperm whale lineage―one that diverged from the main line of evolution to begin a new branch.

Boersma and Pyenson also estimate that A. oxymycterus grew to approximately 20 feet in length, making it moderately sized within the sperm whale family. Unlike many terrestrial animals whose ancestors were larger than their modern counterparts, the modern sperm whale is by far the largest in its family’s history with many mature males exceeding a length of 60 feet. However, whales of comparably large body size to Albicetus have arisen multiple times in the evolution of sperm whales, and the majority of these large whales also have unusually large upper and lower teeth. The only exceptions are the modern sperm whale and its closest fossil relative, which only have teeth in their lower jaw.

The team contends that the presence of big teeth in fossil sperm whales may suggest they were feeding on large prey, perhaps marine mammals such as seals and other smaller whales. Modern sperm whales, on the other hand, currently feed primarily on squid and mostly lack large upper teeth. In fact, many reports of living sperm whales collected on whaling expeditions document pathologically deformed lower jaws in adult specimens, complete with a set of lower teeth, suggesting that sperm whales use their jaws for reasons that may not be related to feeding.

“If you were able to go snorkelling in the Miocene oceans around 15 million years ago, you would have been able to see lots of different species of large sperm whales with big teeth like Albicetus,” Boersma said. “This time in the evolutionary history of whales seems to have been a moment of peak richness in the number and diversity of marine mammals, which may have served as a prey source for all of these whales.”

To accompany their description of Albicetus, Pyenson and Boersma created a three-dimensional model of the specimen. To view and download a model of Albicetus, visit http://3d.si.edu.

# # #

SI-552-2015

Randall Kremer

202-360-8770

Ryan Lavery

202-633-0826